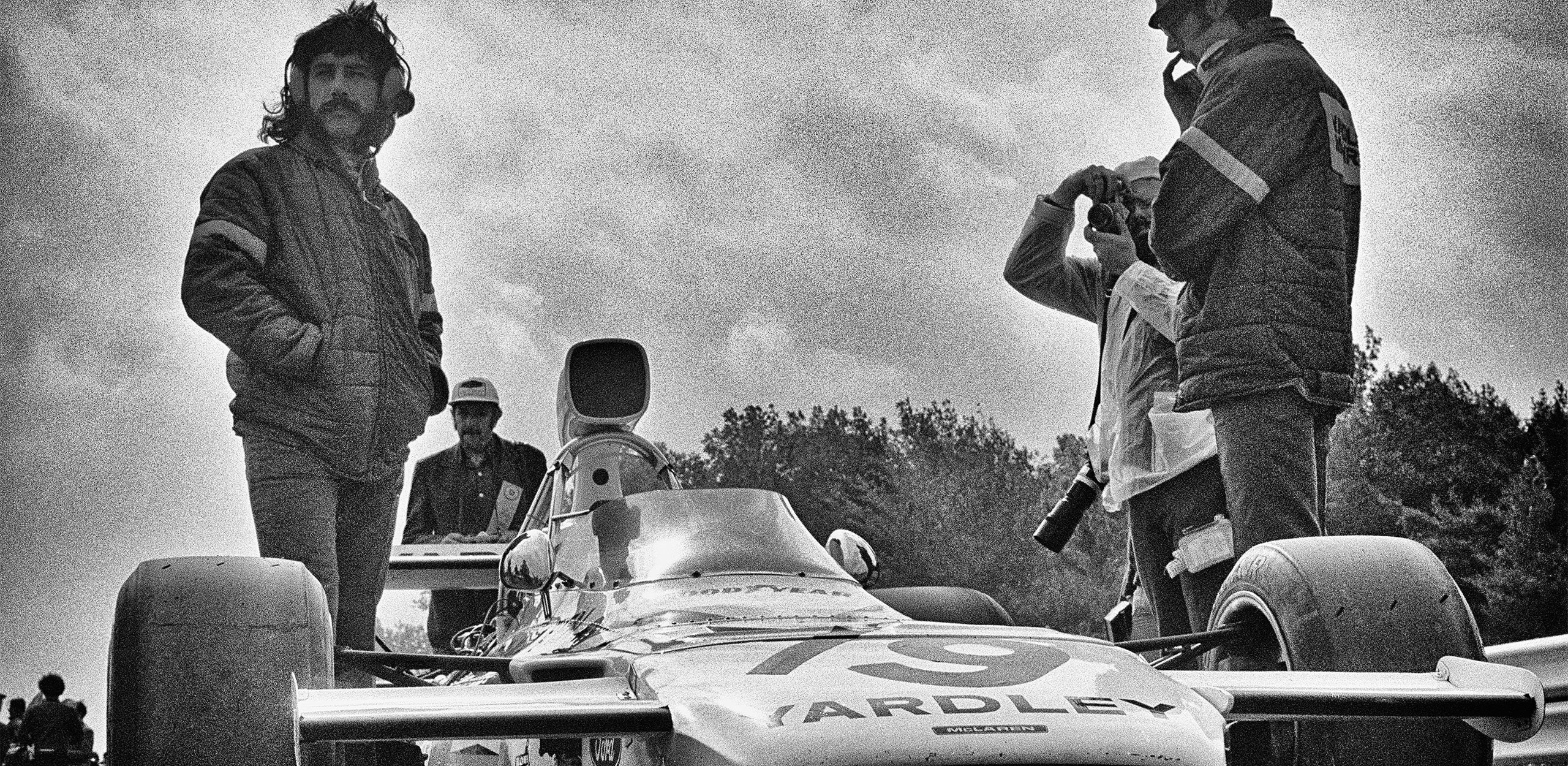

I didn’t pick up a camera until 1971, I was 19-years-old then and a year before I started documenting the F1. I followed a particular set of photojournalists, including Magnum photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson and Eugene Smith. Their visions of photojournalism became my path, and this path had a mantra: make photographs that tell a story. Remove yourself, be invisible, leave out the vanity and make emotional images that point to a truth about your subject. From the moment I was exposed to Formula One in 1969, I decided on the spot that I wanted to be part of that life, however I could.

I could sit down with the drivers or team managers and talk. I could circulate back and forth along the short pit wall as the drivers return to the pits, and at the same time listen to Colin Chapman, Ermanno Cuoghi or Jo Ramirez having a conversation with the crew and the drivers. It was a relaxed atmosphere, cordial and by most comparisons, fairly open. If Jackie Stewart is behind the pit wall with Francois Cevert and I gathered that they were talking about changing ratios or some new problems that one of them have noticed about the track, then they will get the privacy they needed. But I could still catch enough of the discussion to remember it and to use that as a basis for new shots or search for the driver they where discussing to see what his problems were and how he was visually and emotionally reacting to them. The point is that you had tangible access and could hear, smell, react and be immersed in the atmosphere. The teams treated you like a member of their extended family. They saw you as someone who was doing a job that you loved as much as they loved their racing.

I chose “the person” over “the machine” because I wanted to record Grand Prix drivers from a different and unique perspective: to show the mental and emotional strain of a Formula 1 driver trying to go quicker in spite of the yearly flood of new technologies and talents; the pressures to control power; and the exploding cost of keeping one’s seat in the midst of team politics. And don’t forget the ever-present chance of catastrophe. No other sport and very few other endeavors put that much extreme strain and pressure on a person, and “with the person” was where a true photojournalist had to be.

There were always times to talk, but I chose to show respect for their time and their responsibilities to their drivers and teams. Sometimes I would sit around and join the conversation and sometimes it was just a knowing nod and wink, as we already established a connection.

I did learn a lot from Ermanno Cuoghi, Niki Lauda’s mechanic, and most of it will stay with me. He was a genius, a happy man and supremely dedicated to making Niki faster. He helped me see the sport from an insider’s point of view and helped me to be one step ahead of everyone else.

But ninety-nine percent of the time I was just a ‘fly-on-the-wallʼ. I didn’t talk, I just recorded what was happening. I was invisible to them, which allowed my images to be true, emotional and story-telling. That is the way I wanted it to be.

I remember everything concerning where I was and what I heard for each frame, but I have three anecdotes that stick out.

In 1977, I had some photographs that I wanted to give to Niki Lauda from the prior year. I had made good friends with Ermanno Cuoghi, who liked to play practical jokes. I mentioned I was looking for Niki and he smiled, insisting that I to go inside a motorhome to give Lauda the photographs, he even pushed me up the stairs. I entered to find Niki Lauda, Carlos Reutemann and Mauro Forghieri in a very deep debrief. Their stares were absolutely sterilizing. I nodded, dropped the photos and charged out. When I saw Cuoghi, I blurted out, “How could you do that? I wasnʼt supposed to be in there. I never felt so much intensity.” Cuoghi winked, “Now you know what itʼs like to drive for Ferrari these days.” Then he told me that Ferrari had fired him on the spot for going with Niki to the Brabham team.

Then, a week had past from that incident. I was on my way to Mosport when I heard that Lauda had quit Ferrari and that Gilles Villenueve would take his seat. I really liked Gilles from Formula Atlantic, so I looked forward to making some “first days with the Ferrari team shots”. Not so fast – The team physically removed all the photojournalists from the Ferrari pit area prior to the first practice session on that Friday. I remembered that the old pit stalls behind the Ferrari stall had some big cracks in the rear walls. I went outside the pits, circled around, found the biggest crack, put on a zoom lens and waited. The team brought Gilles in, almost covered up, and right in front of my lens, they gave him the Ferrari team jacket and welcomed him to the team. He had a beaming smile and I am the only one who captured these first moments of Gilles as a Ferrari driver.

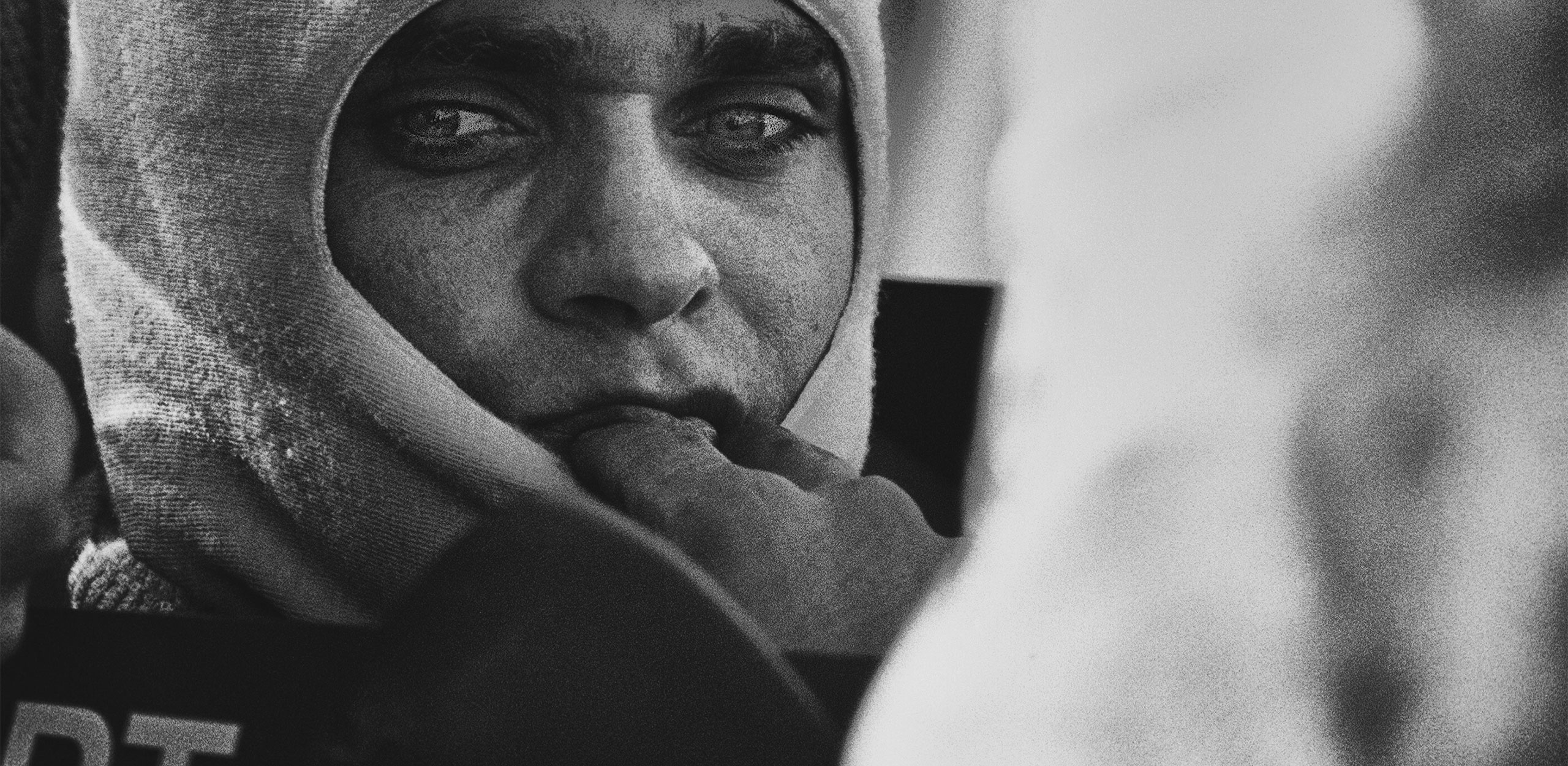

Yes and that is the last anecdote I would like to share. Francois Cevert was on the cusp of greatness at Watkins Glen in 1973. He had already finished second to teammate Jackie Stewart three times during the 1973 Formula One season, and he was about to become Tyrrell’s number one driver, as Jackie had told him of his intent to retire.

I had made some really expressive photographs of him in 1972, and I thought I would try to capture even better images at Watkins Glen. I remember seeing him that morning in the garages: he seemed extremely happy. He picked up Helen, Jackie’s wife, completely off the ground and gave her a hug. The guy seemed bigger than life back then.

At the beginning of practice, I hung around the Tyrrell pit, and Francois suddenly seemed more pensive and quiet. I made a series of frames, each one with him alone and thinking, fingers to his chin. I then went to the rear of the pit stall, to his right. I put on a long lens and waited to see if things would change. Jackie and Derek Gardner approached him and began talking and then they parted; Francois looked at me and then his eyes seemed to look through me. I made one frame and lowered the camera. The intensity gave me chills.

He got ready to leave the pits, looked up at Helen, blew her a kiss, and was gone. I wanted to make shots of him going through the Esses on the back of the circuit and started to walk the road to the access point. Halfway there I noticed that the engines had gone silent. When I arrived, I saw the car and Heinz Klutmeier from Sports Illustrated ran up and said, “Don’t go over. Heʼs gone.”

The shock was devastating; it tore through me like a tsunami. In fact, that particular photograph has haunted me ever since because of my high regard for Francois and my belief he would have gone on to win the 1974 World Championship and change the order of champions for many years to come. He was just on the cusp of greatness.

I have no information on what might have happened to Francois in the pits. He just became very introverted, quiet and reflective.

Francois was using a different approach to gearing for the Esses and I knew that he and Jackie discussed it quite frequently. Francois used third gear there, with the engine high in the rpm band and produced a great amount of torque. Jackie used fourth gear because he favored the smoothness that the lesser amount of torque offered.

Because of the Tyrrell 005 short wheelbase, both of their cars were more worked up in high speed corners, but were much more agile in mid-and-lower speed corners, and that allowed the cars to come off the brakes earlier, balance and then made it easier for the power to be put down and “leap” off the corners and accelerate faster to reach its top speed.

With the nervous nature of the shorter wheelbase, Jackie was concerned that the car would be “too sensitive” in the Esses and chose to use less torque. Francois chose to use more torque, probably to have a better feeling for turn-in with his style of driving.

It was a very dangerous set of corners, with high curbing and very close Armco. It was disliked by Niki Lauda and a number of other drivers. There was zero room for error.

The accident sent a visible shock wave through the drivers, managers, and teams. Francois was universally popular and everyone felt as if they had lost a brother, not in the figurative sense, but the real sense. Many, many drivers were openly weeping, and the pain was felt throughout the sport.

My wife and I watch every Formula One broadcast, every season, even the midnight-2 a.m. broadcasts, because it is part of me and always will be. I have a few close friends who are still part of Formula One, and I follow things very closely.

What I miss is the unpredictability of the races and the chances for a new driver to shine through. I miss seeing the comradeship and the “band-of-brothers” feeling that I felt back then, the respect for others and the common-knowledge that they were all at risk and how that affected their actions when theyʼre next to each other on the track.

I was looking for the real person, the real F1 and within my small part, I think I found it. I wish I made more images, but my funds were extremely limited and most of the time, I wasnʼt able to go where I needed to be. Still, I have over 200 images that are different to the other works out there, and I’m excited that these images, that have never been publicized until now, will at last have a chance to join the history of that amazing era of Formula One.

Richard is F1 photojournalismʼs true “labor of love”. From 1972 to 1984, he covered 16 Grands Prix as a freelancer who went to the races on his own vacation days and was always self-financed. Now, with his new website and a plan for digital compilation, he is sharing his work with true enthusiasts and collectors that recognize the intrinsic content and artistic value of his collection and memoirs.