Look, it’s not easy being Italian. Don’t be fooled by our leisurely approach to life, our seemingly effortless sense of fashion, the smiles, the hugs, the suntans. We are an intense, dramatic people, forged by a history of radical swings between stellar success and spectacular failure. We are not linear, we are not predictable, even to ourselves. And this can be maddening at times.

It seems fitting that this cultural trait would manifest itself most clearly in the realm of motorsports, where the limits of what is possible are constantly being tested as a matter of course. With artisanship as a core component of our DNA, our approach to technology was bred as highly hands-on, and significantly based on gut feelings and the five (or six) senses more than cold calculations and science.

The Alfa Romeo 16C Bimotore is tangible testimony that, in some cases, end results are not always what they seem. Miracles and disasters can come hand in hand, sometimes disguised as each other.

This was never more true than in the fog-shrouded dawn of motor racing; that Cretaceous Era of automotive history, when mighty beasts on spoke wheels roared down unpaved country roads. By the 1920’s, the automobile had fully shed its primordial form of ‘horseless carriage’, and was beginning to come to grips with its newfound and ever-increasing addiction to speed. Pilots wrestled wooden steering wheels in open cockpits, with no proper helmets or roll-cages for decades to come, yet engine displacement, the amount of horsepower, and top speeds were already surprisingly close to the numbers we see today.

France, who had been the first to embrace motor racing at the turn of the century (coining the term “Grand Prix”) soon found its first great rivals in the Italian teams, most notably Maserati and Alfa Romeo, the latter of which was the early stomping ground of an ambitious young driver named Enzo Ferrari.

This period between WWI and WWII was one of great evolution and change for motorsports. Racing leagues were forming, national motoring clubs were beginning to unite into international associations, and dedicated racecourses were emerging as a safer and more controlled alternative to racing on public road circuits. By the 30’s, although Europe was still reeling from the Great Depression, its nations were striving to find their modern identity through drastic political and technological advancements. These were the years of “Formula Libre” in which, as an effort to promote and expand the sport, virtually all weight and power requirements were lifted, with organizers determining rules and regulations almost on a case-by-case basis for each event. As a result, the number of Grand Prix races jumped from five events in 1927 to eighteen in 1934, successfully consolidating motor racing as an international spectator sport.

In 1933, Alfa Romeo, who never had much luck balancing its books, decided to retire temporarily from racing in order to focus mainly on road car production, entrusting its Alfa Corse racing program to none other than Enzo Ferrari himself, under the name of his own Scuderia Ferrari. His main task was to contain the vertiginous ascent of the technically superior German teams, Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, who were running their mighty W25 and Type B on newly-paved Reichsautobahnen, and setting a string of land speed records in the process. This would mark the beginning of another great rivalry in motorsport history, between Le Rosse and the Silver Arrows, one that would last until the present day, extending itself beyond the track, to include the foundry and the chemistry lab. The race had begun to evolve from the mechanical realm into the scientific one.

Thanks to their ability to create new and lighter composite metals, the Germans were able to radically increase the displacement size of their engines (upwards of 4000cc) while keeping overall weight lower than with previous materials. This created a very real challenge for Alfa Romeo, who had until then been very successful with its agile 2.6-litre Tipo B P3 cars. On top of this, Germany had secured an enviable roster of pilots, with Rudolf Caracciola, Manfred von Brauchitsch and Luigi Fagioli racing for Mercedes-Benz, and Hans Stuck, Achille Varzi and Bernd Rosemeyer for Auto Union.

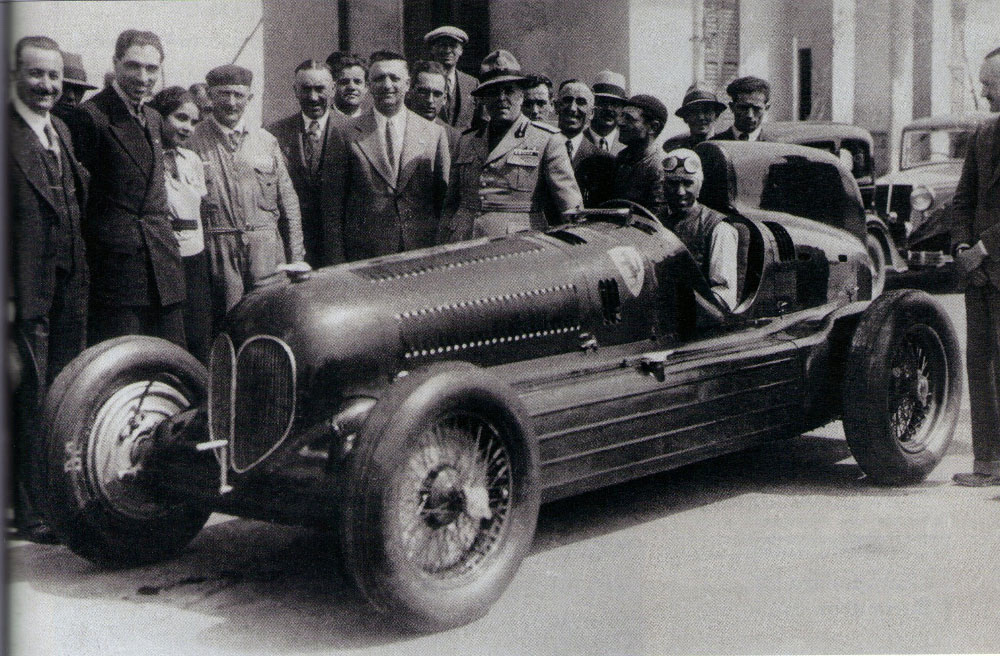

In 1935, faced with this knowledge, and with extreme pressure from the Italian Regime to prove its power on the world stage at the three upcoming Formula Libre events (on the new high-speed circuits of Tunis, Tripoli, and Berlin), Enzo Ferrari had to think fast and, most of all, outside the box. None of the existing Alfas had the sheer muscle to contend with this type of superfast event. A new car had to be built. And despite having two great drivers on the team (Rene Dreyfus of France and Louis Chiron of Monaco), Ferrari knew deep down that only one driver could rise to this challenge. His name was Tazio Giorgio Nuvolari. In Italy, we still call him “Il Mantovano Volante”.

One of the most proficient racers in history, and the inventor (or discoverer) of drift cornering, Tazio Nuvolari was racing for team Maserati at the time. Some say that it was Benito Mussolini himself who demanded that he return to Alfa Romeo that year, but I like to think that it was mostly Enzo’s promise of an unprecedented custom-built race car that ultimately convinced him to come back to the Scuderia.

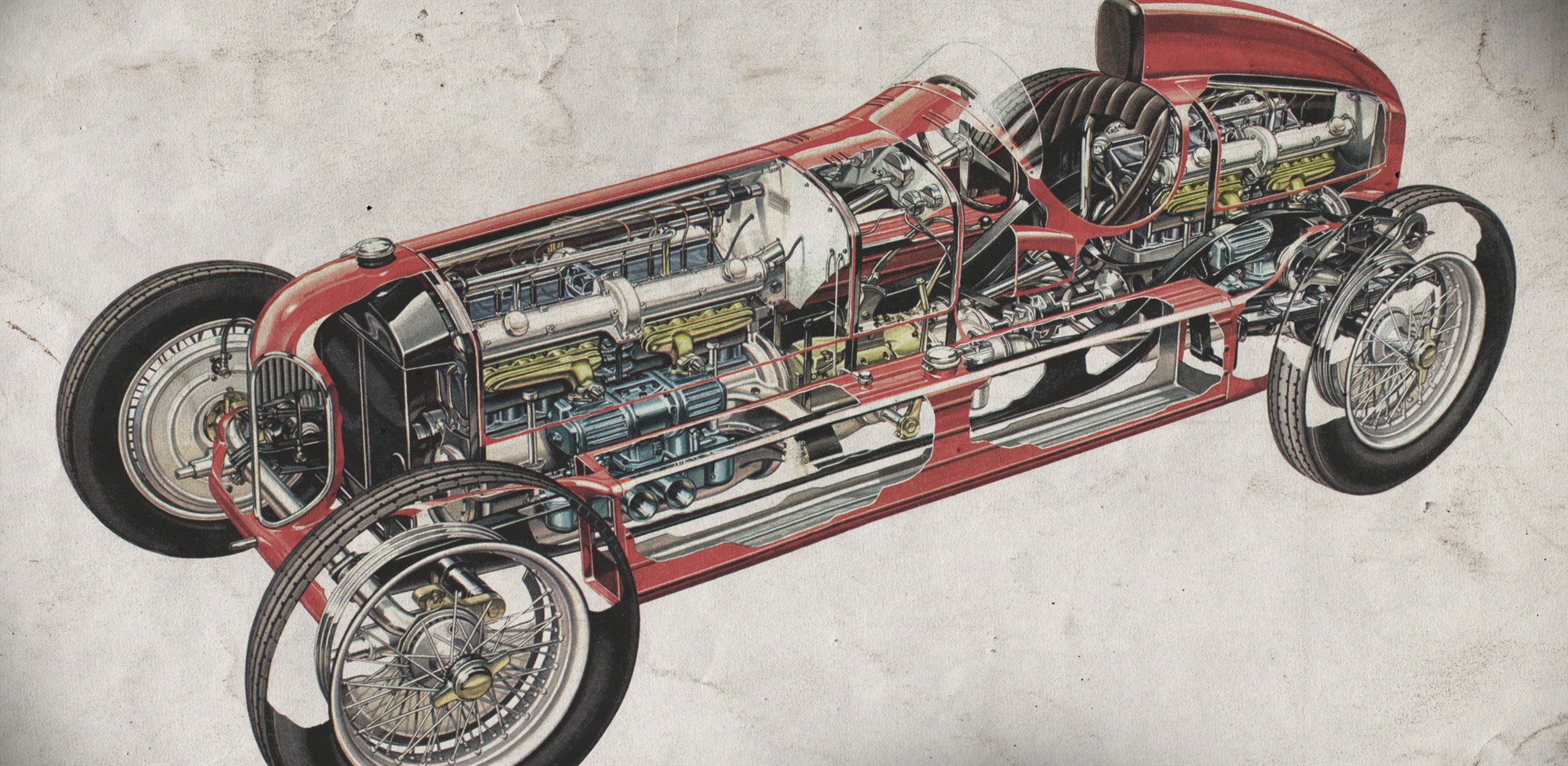

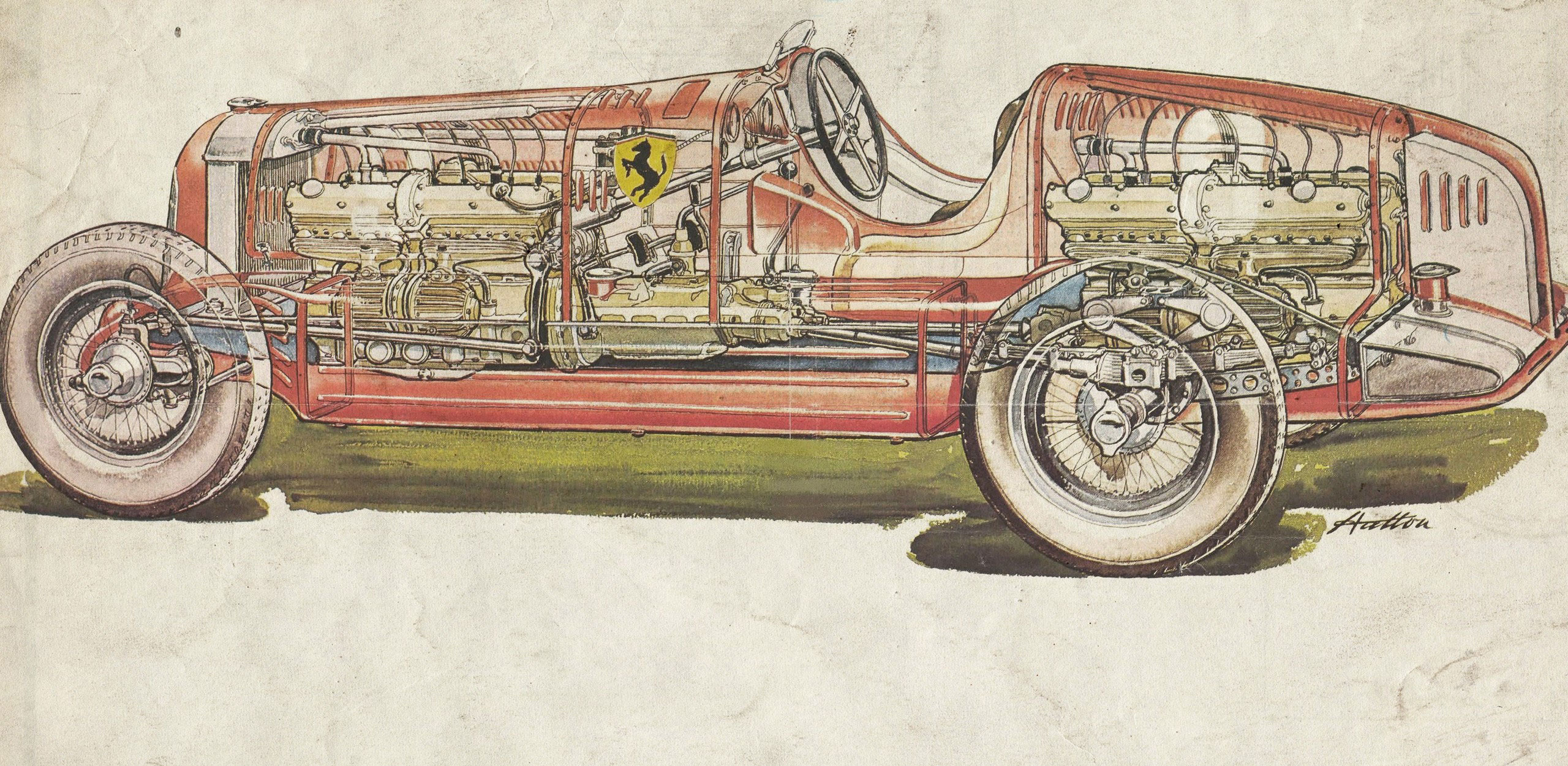

And a truly unprecedented car it was. Weighing in at 1300 kilos, the 16C Bimotore was equipped with two supercharged straight-8-cylinder Alfa Romeo engines (“16C” stands for the number of cylinders), one at the front of the car, and one tucked right behind the cockpit, bringing total displacement to a whopping 6.3 litres, and endowing the beast with 540 horsepower which surpassed both the Mercedes and Auto Union cars (at 430 and 375 bhp respectively.) Some call it the very first Ferrari racecar in its own right.

Now for the bad news. It doesn’t take an engineer to understand that adding a whole second engine meant two times the bulk of a single-engine car. And even more important than the actual weight of the racecar, is how that weight is distributed. At its first test run on April 10 1935, it was already clear that the Bimotore’s raging power and top speed performance (of over 190 mph) came at very high cost in handling, as well as in tire and fuel efficiency. Despite these concerns, there was simply no time to re-design the whole car in time for the three races the car had been designed for.

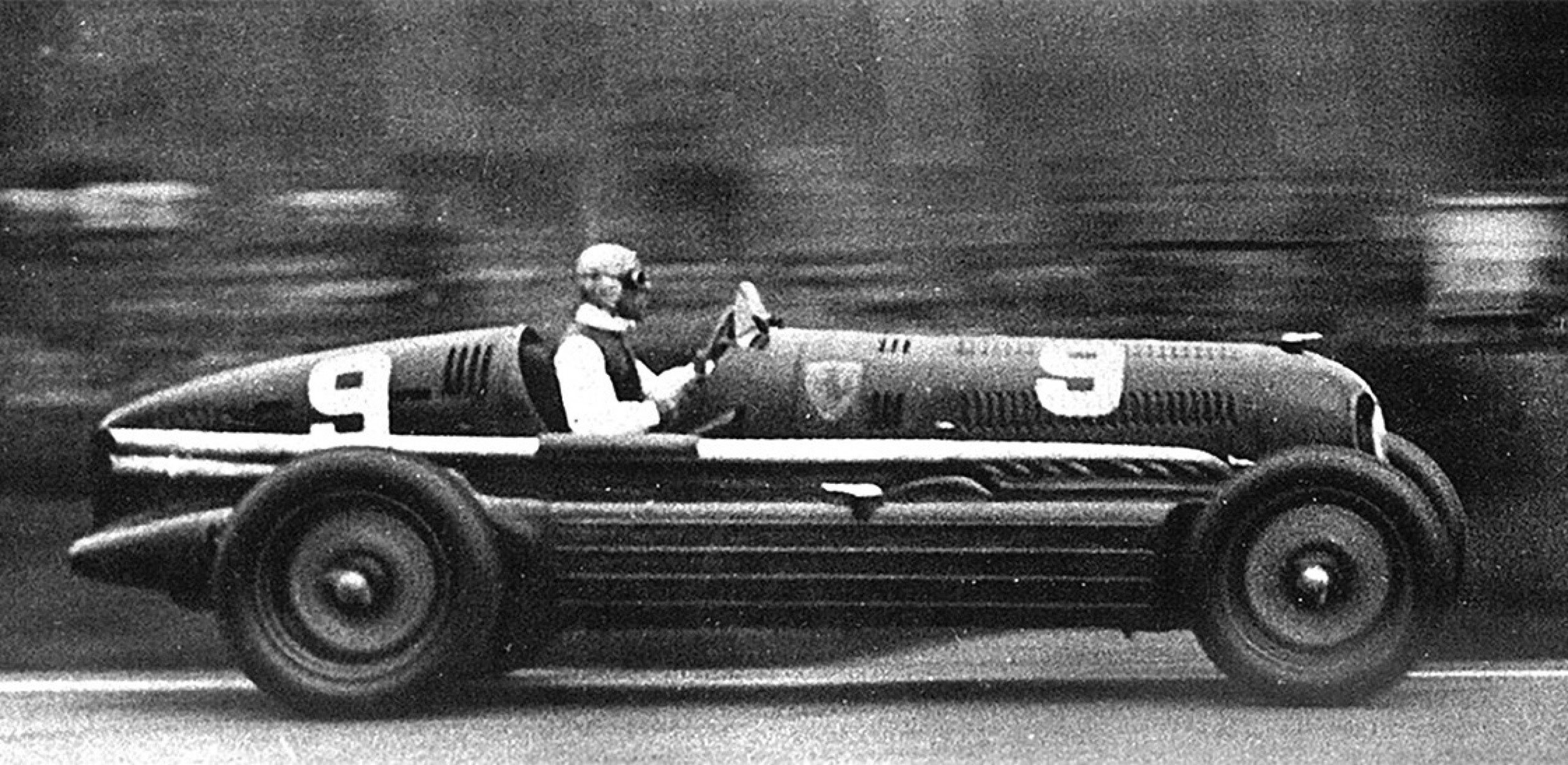

At the Grand Prix of Tunis, last-minute tire problems during testing forced Nuvolari to leave his Bimotore in the pit and race on an obsolete P3 instead, which was out after a few laps and did not finish the race. One week later, at the Grand Prix of Tripoli, the two Bimotore’s of Nuvolari and Chiron only managed to finish fourth and fifth respectively behind the German teams. And finally, two weeks later at the Avusrennen in Berlin, it was only Luis Chiron who conquered second place after Nuvolari failed to qualify for the final heat of the race, again due to the Bimotore relentlessly shredding its tires. Che disastro!

But perhaps not a complete disaster, after all. Before retiring the car, Nuvolari set two land speed records on the Florence-Lucca highway, on June 15, 1935, clocking the flying kilometer at 11.2 seconds, and the mile at 17.9 seconds, becoming the first to break the 200 mph barrier. His top speed on the second run exceeded 362 kilometers per hour, which is remarkable even by modern-day standards. But even without this silver lining, the 16C Bimotore could already be labeled a success as it represents Nuvolari’s return to the Scuderia. Most importantly, the car stands as a testament to that reckless inventiveness that drives motorsports, that will to overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges by committing fully to even the wildest flight of the imagination.